Chameleon breeding explained in detail by an expert

How to breed chameleons

If you’re wondering how to breed chameleons, you’ve come to the right place. I’ve successfully hatched thousands of baby chameleons from 18 different species, have crossed two different species and hatched their hybrid offspring, and have had hundreds of live-births under my care.

I’ve learned a lot along the way—both from failures and successes. There are certain pitfalls you can avoid by learning from those who’ve been there, as well as hints and tips that can make the difference between being successful, and failing.

I’ll go through the various steps including preparation, selection, breeding, gestation, and egg laying. When we’re done, I believe you’ll be ready to try your hand at breeding chameleons yourself. It’s a tremendously rewarding experience, so let’s begin.

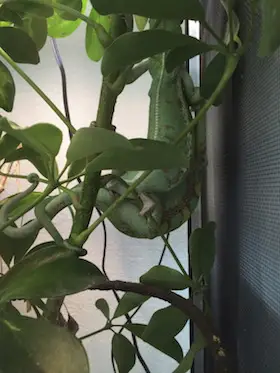

Here are a couple of my Panther chameleons mating.

The female laid healthy eggs 31 days later.

It goes without saying that you’ll need a sexed pair, meaning one male and one female. There are no chameleons that reproduce asexually, although females can lay (infertile) eggs without a male. Any reputable breeder should be able to provide you with a juvenile or adult pair, but it can be more difficult to accurately determine the gender of babies.

My recommendation is to start with a juvenile pair. The reason is twofold. Firstly, you can be more assured of an actual pair, and secondly they’ll be past the risky stage of development. I’d avoid starting with an adult pair because you never know how old they are, and it would be unfortunate to start with a retired breeder. It’s also best to start with a captive bred pair if possible, rather than imports, as there is less risk of stress and parasitization.

Once you have a pair, I’d recommend keeping them in separate cages. While you can successfully keep a breeding pair of chameleons together all the time, there’s a saying: “Absence makes the heart grow fonder.” I’ve found this to be true with chameleon breeding.

Raise your chameleons to adult size before you attempt to have them breed. The reason is, it’s dangerous to have a sub-adult female lay eggs, because her body is still trying to grow. Forcing her to produce eggs, gestate, and lay her clutch is tremendously demanding of her body. In short, breeding your female chameleon before she’s an adult will shorten her life. Patience is a virtue here.

Here’s a pair of my Carpet chameleons mating. The female laid eggs 29 days

later. This is one of the only species I’ve come across that doesn’t have

a high hatch rate in captivity.

Once you’ve raised your pair of chameleons to adult size, you’re ready for the introduction phase. I usually take the female and place her gently into the male’s enclosure, but in my experience it also works vice-versa. The theory is that if you place the female into the male’s territory, he’ll be more aggressive and will want to show his dominance by breeding her.

Monitor the female closely. The next several seconds tell you everything you need to know about whether mating will take place. Mating will only be successful if she’s ovulating, and it’s not something that’s always visually apparent. The only real way to tell if she’s receptive is to focus on her reaction to the male.

The male will immediately take notice of her and will most likely start moving towards her. If she’s not receptive, she’ll either quickly try to run away from the male, or she’ll start gaping (hissing with mouth open) towards him, or both. If she’s receptive, she’ll walk slowly, and will seemingly not pay much attention to the male’s advances. She’ll then allow mating, which takes anywhere from 5-30 minutes.

If she’s not receptive, remove her immediately because she could get injured by the male, and try again in a few days. If she is receptive, allow the chameleons to breed for 30 minutes or so. If you want to be thorough, leave them together for 24 hours and then remove the female.

Breeding chameleons - Step 3 (Gestation)

Congratulations, you’ve now witnessed your chameleons breeding! Believe it or not, that’s the easy part.

Now begins your female chameleon’s gestation. This fairly brief period is when the eggs will develop and be shelled inside her. Gestation usually lasts around 30 days, +/- five days or so, for most species I’ve bred.

There are a few chameleons that have substantially longer gestations. I remember I had a freshly imported Sailfin chameleon (Trioceros cristatus) that was beautiful, and very plump. This was the first time I had kept this species, but I was sure she was going to lay eggs any day.

One month passed. Two months passed. She finally laid a clutch of beautiful white eggs over two months after she had arrived looking fully gravid. “Gravid,” by the way, is basically another way of saying “pregnant.” Egg-laying animals are generally referred to as gravid instead of pregnant. The eggs all hatched successfully.

Gestation is a very important period when breeding chameleons. This is when the female must be given more food and more supplementation than normal, because her body is preparing the eggs for their journey. Garbage in, garbage out.

I offer my gravid female chameleons as many crickets as they’ll consume daily, and I throw-in some waxworms, roaches, and hornworms along the way as well. Just use common sense. I don’t determine how much they can eat, I let the chameleon decide, and I’ve never had an obese chameleon.

Since the gravid female’s body will be forming shells, make sure you’re dusting her feeder insects with a quality calcium supplement 2-3 times per week. I use Repashy SuperCal NoD and LoD, but there are a few quality brands out there. I’ve used Miner-All with success as well. Make sure you’re not dosing her with much D3, too much can be dangerous for her health.

Here’s another pair of my Panther chameleons breeding, making

babies to be enjoyed by chameleon enthusiasts all over the country.

Here are a pair of my Elephant Eared chameleons

(Calumma brevicorne) mating successfully.

A pair of my favorite Veiled chameleons

(Chameaeleo calyptratus) breeding.

The gestation period ends abruptly when the female chameleon is ready to lay her eggs. While you might wonder, “How on earth do I know when my chameleon’s ready to lay eggs?” it’s actually very, very simple. Just pay attention to her each day, and when you see her on the floor of the cage—boom, it’s go time.

Why is this the telltale sign? Well, chameleons are mostly arboreal (tree-dwelling), so it’s very unnatural and awkward for them to be on the ground. In other words, the only time they’re on the ground is when they’re looking for a place to lay eggs.

Have her laying bin prepared ahead of time. Here’s how I put mine together. Find a large plastic bin, the kind available from Home Depot, Lowe’s, Walmart, etc. Mine are about 24” x 18” x 18” (L x W x H). I then fill it with a mix of peat moss and sand, at about a ratio of 3:1, respectively. Fill it to about 8-inches deep, compressed. In other words, keep pressing down on the substrate and adding more, pack it down, and add more, until it’s about 8-inches deep.

Now, you can place your gravid female chameleon into the laying bin. I place the cover on the top so that it covers about two-thirds. You want some light to enter the bin, but also a lot of dark privacy. Now, leave her alone. If she sees you peeking in, she may abandon her laying spot.

I attach a remote video camera to the top edge of the laying bin so that I can monitor the chameleon in a clandestine manner. In other words, I can check in on my iPhone and see where she’s decided to lay her eggs. Often times it’s in the evening or at night, which makes sense from a predator standpoint.

Once you check in on her and she’s smaller and there’s no more hole in the dirt, you know she’s laid her eggs and has covered them up, which they’re very efficient at doing. One of the reasons I monitor them via remote video is because if I didn’t know where she initially dug her laying tunnel, it’d be almost impossible to know. Since digging them up is such a delicate process, you want to know where to begin digging.

Here’s one of my hugely gravid Panther chameleons.

The females get a bright orange stripe on either

side when they’re gravid.

Here’s one of my Carpet chameleons laying

eggs in the hole she just dug.

Now that your female chameleon is back in her cage, it’s time to start digging. I use my hands—no instruments at all. This is because “touch” is very important. I sweep my fingers, palm-down, rapidly (but gently) back-and-forth and slowly excavate the substrate into piles until I see the white of the eggs.

It’s rare that you’ll fine eggs within two inches of the surface. They’re usually 3-8 inches deep. Some species lay deeper than others—Veiled and Oustalet’s chameleons are the deepest egg layers I’ve come across.

Once you find your chameleon’s eggs, start carefully collecting them and placing them into the incubation container. Don’t rotate them from the original position you find them. So, whatever end is facing up, make sure it remains facing up in the incubation container. I use a pencil and mark the top of the egg so that I know its original position.

Good eggs are bright white and taught. Bad eggs are discolored and yellow. But, you never know, so don’t throw-out poor looking eggs. If the eggs are bad, they will collapse and mold within a few weeks.

Perlite is my incubation medium of choice—it’s served me very well. I mix perlite with water. I don’t use a particular mixture calculation, I just add enough water so that the perlite is very slightly damp, but not wet. I don’t use vermiculite because it can contain asbestos. I’ve read that this only applies to one mine in the Northwest, but regardless, I don’t risk it.

I fill a plastic shoebox about halfway with perlite, and then I mix-in about one cup of water. You can use tap water, that’s what I use. Some folks use spring or distilled, but I’ve never had an issue using tap water. If you don’t want to use tap, I’d use spring water since distilled water has all minerals stripped-out.

Chameleon egg incubation periods vary greatly, but it generally it takes 6-8 months for them to hatch. Pygmy chameleons can hatch in three months, while Parson’s can take well over 18 months. But, generally speaking, you’re usually looking at 6-8 months or so—this would include Panthers, Veileds, Oustalet’s, Verrucosus, Flapnecks, Fischer’s, Cristatus, Quadricornis, Jackson’s (live birth), Werner’s (live birth), Rudis (live birth), etc.

Some people mess around with the incubation temperatures, bringing them up, then down, etc., in an attempt to mimic seasons in the wild. But, I keep almost all my eggs in a large room at our facility, at room temperature. I’d say it fluctuates naturally from around 68F to 76F depending upon the time of year. This has resulted in absolutely stellar hatch rates of around 85% to 100%, with the notable exception of Carpet chameleons, which were closer to 33% or so.

The main advantage of incubating your chameleon eggs in a room is that the temperature never fluctuates quickly. Inside a small incubator, the temperature can increase several degrees in a matter of minutes—that generally doesn’t happen in a room. I’m of the belief that quick temperature changes are what’s dangerous to chameleon eggs, but not slow, very gradual temperature changes. I don’t trust small incubators whatsoever.

Successful chameleon breeding results in quality eggs. These eggs get harvested and placed into an incubation container, as discussed above. The eggs then will actually grow over the coming months. How is this possible when the chameleon egg is already a certain size with a seemingly hard shell?

Chameleon eggs absorb water throughout incubation, and the shell is more flexible than you’d think. Definitely nothing like a chicken egg. The egg will slowly expand, often times doubling in size, over the course of several months of incubation.

Keep an eye on the eggs—I check mine every day or so. If there’s too much condensation building up, you have the incubation medium too wet. If the eggs start “denting,” there isn’t enough water in the media. Denting, which means is usually reversible if you catch it within a few days. If there’s a deteriorating egg, remove it or it’ll produce ammonia that will lay low in the container, potentially affecting the other eggs.

When your chameleon eggs are about ready to hatch, they’ll sweat. This means you’ll notice little droplets forming on the surface of the eggs. Once the babies start hatching, it tends to signal the other eggs to start hatching. I let the baby chameleons roam inside the incubation container for about 24 hours before I remove them.

Here’s what you end up with after a successful

incubation: a healthy baby chameleon

When one baby chameleon emerges, the rest

tend to follow suit quickly.

The above instructions on how to breed chameleons applies generally to most species. There are always exceptions, but if you’re dealing with the rarely seen species, you’re probably already quite advanced. The key is usually introducing your female to the male at the right time, because as I mentioned earlier, she must be ovulating to become gravid.

A recommended method for getting your female chameleon into breeding readiness is to lower the temperature of the chameleon room by several degrees, for about 2-3 months. Ideally this coincides with your natural Winter period—trust me, it makes it much easier when you just follow your own local seasons. This will naturally lead to less food, and less activity. After 2-3 months, warm the temperatures back up (simulating Springtime), at which time the chameleons are usually ready to breed.